I’m OK, You’re OK. Filtering the Intensity of Life: A conversation with Mariken Wessels on Taking Off. Henry My Neighbor, in the presence of Taco Hidde Bakker

Mirelle Thijsen (MT):

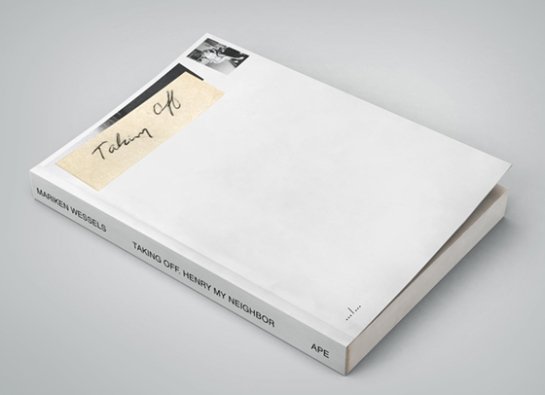

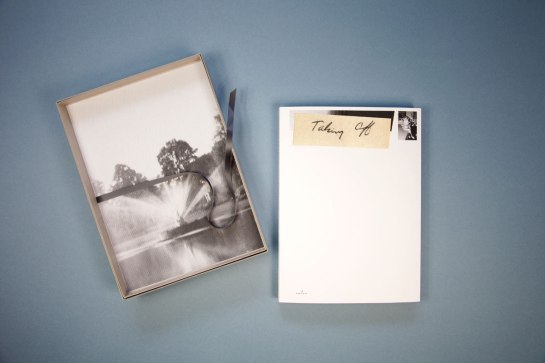

Taking off. Henry my neighbor, your recently published book – launched at Offprint in London (in Tate Modern‘s Turbine Hall) and at Amsterdam Art Fair with Johan Deumens Gallery – was published five years after Queen Ann. P.S. Belly cut off (2010) and seven years after Elisabeth – I want to Eat (2008). The three artist’s books, of the same size and format, together form an ‘open trilogy’. Trilogy is an interesting term, knowing it from the world of theater and literature, and in a way coming from your background in acting. A first question: to what extent are the publications thematically linked as a group of three ‘dramatic or literary’ works?

Mariken Wessels (MW):

I designated it a ‘trilogy’ because my approach relates to theater insofar I work with characters like Elisabeth or Ann, or Henry and Martha for the new book, based on archival materials I received. Like a performer creates an environment, you build credibility by responding to questions as: who am I, where do I come from, why am I here, where do I go & what do I want? Being able to answer these one makes an analysis of how characters develop and mature.

In case information lacks I add to it, so to answer questions, like ‘where does he live and what is he like?’ Each time I write a script and gradually shape characters from notes, memos and sketches. Failing items are drawn from other sources, because I consider the material valuable for making up a partly fictional though credible character. This doesn’t apply to my other books. He was there (2012), for example, is a photobook for which I took pictures myself. At other times I collect pictures online. But Taking Off starts from the dramatic principle, that in creating a full-grown character everything has to match.

In terms of similarities: in all three stories, there are one or two protagonists. Elisabeth communicates with her aunt who tells her via postcards that she is crazy and has to face life. Eventually one wonders who the crazy one is. It’s an interaction between two people, like with Henry and Martha too. Martha took off her clothes before Henry’s camera. She chose to do it but could have said no. Queen Ann tells a different story: Ann is self-destructive and in conflict with the outside world, she decided to cut away her fat belly.

A common thread is that all protagonists wrestled with shame. You wonder how it’s possible that someone is interested in exhibiting their privacy like Ann did. Her story stands in stark contrast, for example, to today’s reality shows. All three narratives touch upon the edges of privacy.

MT:

You mentioned writing a ‘scenario’ for Taking Off, does that apply to each part of the trilogy?

MW:

It’s not really a ‘scenario’, I describe characters and role profiles, based on the archive I got and the research I did. First I note down facts such as age, address, profession, movements and background. In theater this approach is known as the Stanislavsky Method. If you can’t distil these facts from existing documentation (in Chekhov’s Three Sisters it’s not all spelled out either) you need to find them out, but much is up for self-interpretation.

MT:

That explains the term: ‘open’ trilogy.

MW:

Indeed it does.

MT:

From a bird’s-eye view you played with a voyeuristic approach in He was there (2012) and made reconstructions of your deceased brother’s life in WHO (2012). Every artist’s book seems an effort to remember and assemble images displaying lives of anonymous people, characters if you wish, based on personal memories but infused by imagination. In general, an effort to ‘keepsake’ (a title of one of your projects) meaning ‘anything kept, or given to be kept, as a token of friendship or affection, remembrance.’ At the same time these personal stories are altered narratives. A trained actress you later entered the world of photography, dealing mainly with amateur photography. Correct me if I’m wrong: you make pictures of other peoples’ pictures; step into someone’s life so to create a fictional character, as performers do.

MW:

Yes, I appropriate materials from personal archives, creating characters, yet staying true to the source.

MT:

Focusing exclusively on amateur photography?

MW:

Not per se. I use self-made images, which I then often rephotograph. I try to find a fitting ‘translation’ for an absent image. Provenance doesn’t matter; whether I take the picture myself or take it from an archive, if it suits a character, anything goes. It’s often amateur photography because that genre, for all its unpretentiousness, speaks straight from the heart.

MT:

How do you cast a role, create a person in writing? Do you describe the missing pictures?

MW:

I pull images from an obtained archive from which I start building a character. I collect as many facts as possible. At one point in Taking Off Martha spreads her arms, symbolizing liberation. I removed this image from its original context. By re-contextualizing, cropping and placing it elsewhere, it gains another kind of suspense. How I made that decision? I needed that image because I knew she did step out of her situation, hence I started sifting the archive.

MT:

So beforehand you visualize a mental image?

MW:

Yes, in terms of direction, with regards to existing material; to keep it authentic.

MT:

But the archive is a fragmentary entity, perhaps stored in a box?

MW:

It’s a starting point for creating a narrative. While investigating the archive the storyline gets nurtured by observations. I verify by reading documents, by talking to people involved, and for example after having found Henry’s annotations, I realized he was an amateur photographer. These elements form a plot thread.

MT:

And the notion of ‘keepsake’, which is so vital to your work?

MW:

I’m fascinated and emotionally triggered by ephemeral lives. In trying to retain time, hold on to memories, one realizes that life is fleeting. While it’s a work about him, there are no pictures of my brother in my book WHO. I got no pictures of him after he passed away. Instead WHO was compiled from images I found online, where I looked for images that would bring his house back to memory. Of course I knew what it looked like: I just could have biked over there to have taken a look…but this would have been a huge move, too intimate. I then collected images so to reconstruct how I used to arrive at his place and what it did look like. Now while talking about this, I regain these images, seeing his guitar for example (he had many guitars, but not the one depicted in the book).

MT:

You create distance from what has happened in real life and drape your imagination over it, adding experiences to a personal life; we could perhaps say it’s a falsification of personal history?

MW:

Yes, and maybe because reality is too fierce. It’s a way to filter the intensity of life. Maybe ‘the third person’ helps in creating a storyline, in compiling a publication; because just the naked thruth that Henry had taken nude pictures of Martha for over two years raises an aversion. This is reality, it’s part of life and I feel I detest it. And this story reflects just a fraction of what happens in real life.

MT:

Let’s take a closer look at your book, starting with the title. What does Taking Off stand for? You discovered the archive of an extravagant amateur photographer named Henry, and who obsessively took and categorized nude photographs of his wife.

MW:

The title comes from one of Henry’s annotations. It could have also been ‘squeeze’, ‘kneeling’ or ‘xx good’ (some of his categories). But I thought the double meaning of ‘taking off’ was more fitting.

MT:

Exactly. Where did it originate; when did Henry start his amateur-nude-art-practice?

MW:

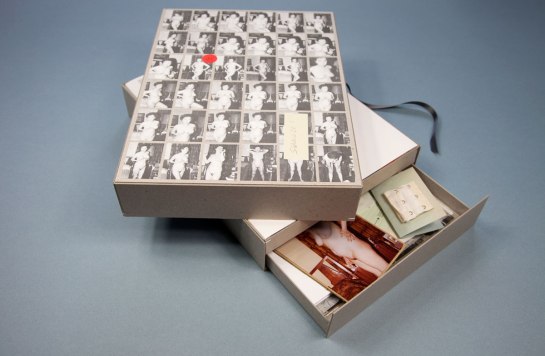

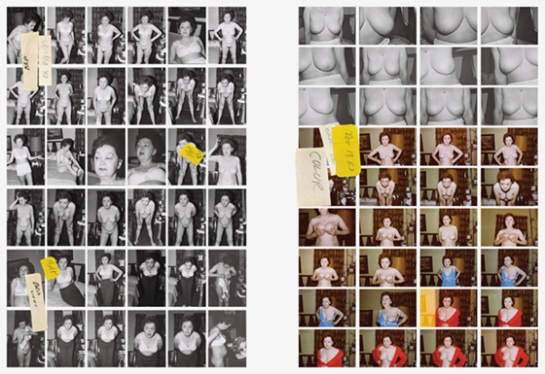

You’ll find the answer in the handmade diagram, which is part of the archive and reproduced here full-scale. From February 1981 till November 1983 Henry took 5,500 nude photographs. The categories correspond to annotations Henry made on the contact sheets. A husband who uses his wife as an object. Intimacy was absent is the impression one gets. It was Henry’s project, in which he was obsessed with lenses, film types, and judgment: ‘good’, ‘okayxx’ is what he noted down, a practice which is perhaps even more fascinating than the pictures themselves.

MT:

Let’s go back to the moment in which you found yourself in possession of a wealth of material. I understood from a short text in the book that while living close to New York City you met Edward F. Carroll and Dorothy Bartlett, ‘close friends’ of Henry and Martha. When did you live in the Long Island suburbs? When and where did you meet Edward and Dorothy? What did they tell about your former neighbors?

MW:

Facts aren’t important, otherwise I would have mentioned all of them. It’s an open approach, you might find the facts in the story itself. It was not my intention to make a straightforward documentary.

MT:

Would you want to lift a tip of the veil and explain how you met these people and where the material was stored?

MW:

No, not really. The project has been long in the making with long pauses in between… And this final result is what I wanted to publish. For example some collages were left out. Besides, some of your questions are answered in the epilogue.

MT:

Let’s put it differently: you were notified about the archive but left the material untouched for quite some time; it feels like an incubation period. How does it work?

MW:

It sat idle for quite some time indeed. Generally I leave material untouched for a while, in order to conceptualize and take distance from its source, making it easier to appropriate. When the moment is ripe and I’m able to keep the protagonist at arm’s length, I start to implement the material into my story.

MT:

Are you willing to reconstruct the first time you encountered Henry’s archive? In terms of personal experience?

MW:

I was enthralled right away and recognized the material’s potential.

MT:

What’s your fascination: How these people treated each other, how they communicated?

MW:

In fact, I already worked on another project related to ‘neighbors’, about stuff that happens behind closed curtains. What do we know and not know? After being allowed access to Henry’s archive, I knew I could use it and it also proved appropriate because luckily Martha isn’t particularly beautiful, for if she were I wouldn’t have used the photographs. The mediocrity appealed to me. As for the general theme: I’ve had a long-lasting fascination with people leading double lives.

MT:

How come?

MW:

I presume it relates to what we deal with in the world. You watch television and see a good looking man, you consider him a kind person, who actually happens to have been keeping children imprisoned in some basement.

Taco Hidde Bakker (THB):

It’s also about the friction between private and public domains, a person’s decorum: about how you present yourself to the outside world.

MT:

In that sense, the red thread is ‘acting’: decorum keeps up a mental attitude, a personage. Each of us is distorted by conditioning, personal traumas, indoctrination, etc. This specific behavior as exposed by Henry seemingly had to do with his past, his maternal bond.

MW:

All three publications deal with these social and behavioral aspects; with distortions of behavior.

THB:

And how the camera heightens tensions between private and public domain….

MT:

The camera is an important vehicle; in particular with regards to amateur photography: its own record must be irreproachable within the private domain. My next question probably will be too much focused on the facts as well: Where did you find the material and what did it originally look like?

MW:

I presume the book offers the reader details about the different domains I was given access to.

MT:

We will discuss the different ‘acts’ shortly. It relates to what you describe as ‘editing and rearranging’ Henry’s archive. How did you channel the extraordinary amount of pictures: 5,500 black-and-white photographs and 40 collages? What went through your head while processing the material?

MW:

I depart from materials at my disposal. I started with arranging and sorting out Henry’s work chronologically, following from his annotations.

MT:

During this process you were already aware of the personal histories of the protagonists?

MW:

Information I obtain gets sorted out and rearranged into a new structure. I construct the narrative based on my analysis of everything available. Upon reading the annotations I concluded that Henry must have been an amateur photographer knowledgeable about film and lenses and such. I collect, categorize and puzzle for a while, so to compile a narrative.

THB:

But things that you received are not by definition chronologically sorted…. In fact you translate ‘archive’ into ‘narrative’.

MW:

Yes, that’s the kind of process.

MT:

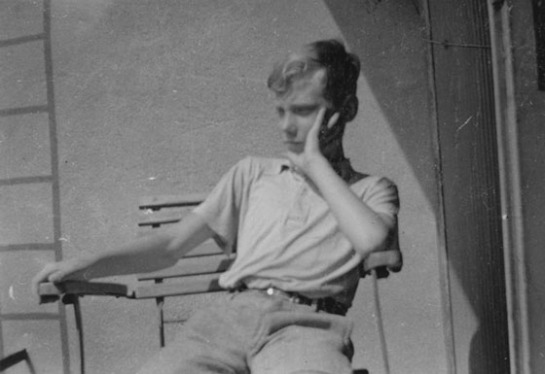

I’m not sure to what extent my next question will be answered: Looking at the photo of Henry the adolescent, in his polo shirt, he seems so innocent but also not quite at ease, perhaps even a little vain. And I realized this is the boy that became Henry. It’s fascinating: a single youth portrait gets a different dimension. What type of person was he? Do you have information about his life, youth, and his profession?

MW:

He worked as an electrician. In the foldout pages of his room you’ll find the same portrait again. You’ll find more there, for example a book titled I’m OK, You’re OK. And he was obsessed about survival strategies, he owned books about how to control life; how to stand firm. Also, looking at the youth portrait: I see someone despondent, neither pleasant nor reliable.

MT:

Upon opening the book you realize right away that ‘Henry’s wife’ is the protagonist. The book is dedicated to her. What was her life like? You wrote that she was ‘under his spell’. You already indicated that Martha was submitted to stand model for her husbands’ compulsive behavior for a period of at least two and a half years. How did she abide with her husband’s behavior? And about ‘In dedication to Martha. For her courage’, the book’s opening lines: What makes her courageous?

MW:

It’s my opinion about her. She has traits of a submissive personality. Her face in the pictures expresses apprehension. But she found the courage to break the negative spiral. In one image we see her going upstairs to the room, close to opening up what was kept from sight. After having discovered the room, she became aware of what she partook in and broke out. Who knows about what happened before all this? Perhaps part of the archive was discarded; that’s why I don’t just cling to facts. Then there are feelings of shame, inasmuch as making a victim of rape into an accomplice, a partner in crime. Victims of sexual abuse often only seek publicity many years after the fact. It’s part of overcoming feelings of guilt and shame, as if having been accomplice to the crime. Likewise Martha overcame feelings of shame, and to throw the pictures out of the house was her way of dealing with it.

MT:

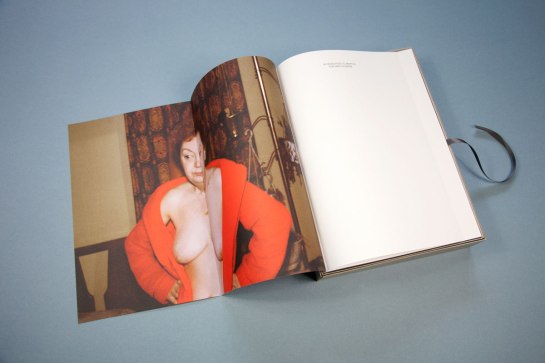

The first picture, a large color photograph inside the front cover, shows Martha in an opened bright red duster, with a pale skin, freckles and large breasts. She looks away from the camera. Why have this image begin the puzzling narrative?

MW:

This was the last session, the last time she has been posing. She is introduced and simultaneously it reveals the moment she decided: It’s Enough! It’s the only time she wore red, a color I associate with bull fighting and with breaking out. She looks at the camera asking: “how do I get out of here?!”

MT:

What follows is the first act, which is quite disturbing: large-format full spreads showing grainy and uncanny black-and-white images, starting with a baby in a bathtub. And what happens next? Could you comment on the first 10 spreads, followed by two coal-black pages, and a Japanese-bound foldout, cleaving a foreshortened portrait of Martha, her youth portrait hidden inside. It feels like something bad is about to happen… gloom and doom… In short: a dark youth.

MW:

The black pages represent the story’s intensity. After the double portrait comes a picture of Martha covering her head and face with a scarf. Resistance maybe started here.

MT:

Followed by pictures showing frustration about undressing and being put in awkward positions. It’s a struggle, she’s not at ease. A strong statement. I presume these were the moments just before posing?

MW:

That’s correct, although you may find the same pictures in the contact sheets. In terms of chronology things are different, but I re-contextualized them with that in mind. It’s a preview of things to happen. The picture of Martha going upstairs is crucial, she is literally going to enter the room, but will also be confronted with what has been surpressed for years.

MT:

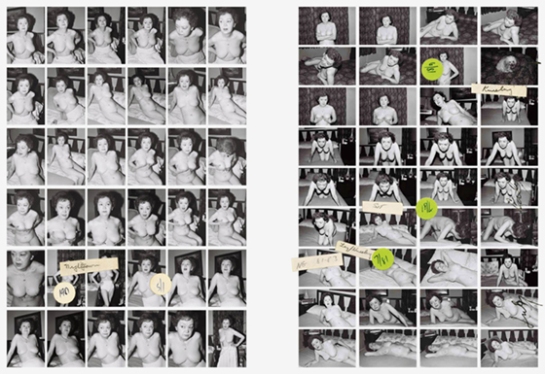

The first act is about traumatized youth, the second act about Martha pulling faces and taking off her clothes. The third act is made up by an avalanche of images: grids of similar nudes reproduced on glossy paper; categorized and labeled with stickers stating ‘sitting’, ‘bust’, ‘going flat’, ‘night gown’, ‘good bra’ etc. An overwhelming amount of pictures, like repeating a dry exercise: stand up; lie down; press up breasts; sit on hands and knees; always before the same backdrop: a bed, dark curtains, copper flower pots, a shaded lamp. The images are far from being erotic or pornographic, it rather looks like domestic photography with a high Hans-Peter Feldmann level (in All the Clothes of a Woman (1970) Feldmann piece by piece photographed all the clothes of a lady friend, like product photography, objectifying but also representing a personality).

MW:

There is a Feldmann association in the sense of summing up, choosing shoes or clothing. I considered it necessary to print the entire series, to show the couple’s obsessive behavior. Henry’s practice also reminds of Muybridge’s ‘Animal Locomotion’: sequences investigating subsequent phases of animal and human movement. I find the study and cataloging of human body positions fascinating.

MT:

At some point we see a white curly poodle on the bed. Their pet, isn’t it?

MW:

Yes. The dog appears multiple times. He’s a witness.

MT:

After the grids, on a double spread there is a handmade diagram, indicating dates, body positions and photographic techniques used. Henry mirrored different labels in order to read them on both sides of the chart. Is that correct? Where did you find this document?

MW:

He used carbon paper with a blue-pigment coating; the listing in blue was printed through carbon. I found the original document. It is one scheme whereby sections of the offprint were pasted onto the original typewriting.

MT:

Then follows the next act. We see a picture of someone in a raincoat, seen from the back, opening the door to Henry’s ‘workroom’, echoing the picture of Martha going upstairs. A foldout shows the room with nude pictures all over the place, like wallpaper. I also discovered some book titles, making me curious to what Henry read: The Amazing Laws of Cosmic Mind Power and Your Erroneous Zones. The latter meaning ‘If you’re plagued by guilt or worry and find yourself unwittingly falling into the same old self-destructive patterns, then you have “erroneous zones”’. The photograph of his workroom contains a wealth of information.

MW:

Like the other books, such as: I’m OK, You’re OK, they’re guides on how to gain control over life and how to foster optimism.The picture shows what has happened on Henry-territory, where besides having printed contact sheets he made annotations on a typewriter. His obsession, expressed through thousands of prints, is most tangible in his study.

MT:

What is depicted on the double page where the letters ‘taking off’, printed on a plastic strip, are blindfolding a picture of Martha?

MW:

That’s a section of the study with the strip glued to the wall. Henry made annotations and put them on the wall. These images are close to being collages already; photos pasted atop each other.

MT:

Then the window opens and pictures are thrown out onto the street. Some neighbors might have witnessed the scene.

MW:

Yet another pivotal image: Martha throwing it all out, beyond shame… neighbors made witness to these disturbing facts. Her liberation entails more than Henry’s: no more hiding, no matter what people think. She comes to stand above all this.

MT:

We get to see a ‘liberated’ or ‘crucified’ Martha next, pale and tired, followed by a picture of a white peacock, seven blank pages and finally a picture of a roll of white paper towel. We move from black to white. What does ‘white’ symbolize?

MW:

It represents a new phase: eruption. There’s a crack where the light gets in. The outside world is invited; a shift occurs. As for the paper towel: washing your hands clean refers to what I consider the most intriguing part of Macbeth: after Macbeth had killed King Duncan on Lady Macbeth’s behalf, she compulsively kept on washing her hands, in a ritual of purification.

MT:

Like Pilatus washing his hands in innocence…

MW:

Yes.

And here you’ll find the inserted loose-leafed letter, where it belongs.

MT

Why?

MW:

Because Henry wasn’t feeling well, unable to share his emotions. His room was chaos; he started cutting and pasting the tattered images. Everything shifted, but to the outside world he acted as if nothing happened. The letter expresses his attempt in keeping everything under control.

MT:

That explains why the typewritten letter is inserted here with the semi-demolished room.

MW:

‘Everything is fine, it’s all under control’ is what the letter seems to tell: ‘I’m OK, You’re OK’.

THB:

He wrote about himself in the third person; creating distance.

MT:

What about the provenance of all the material? In this trilogy it got detached from its source. You rely on making associations. To what extent, then, does the story qualify as ‘a real picture story’? (as quoted from your website.) In other words: what’s true or untrue?

MW:

What’s truth? Everything considered true might not be true after all. Maybe Martha did ask her husband to photograph her extensively… I also could have inverted the plot, with Henry being the slave. And what’s a real life story in the newspapers? Each of us filters news differently. This book is presented as a documentary and at the same time raising the question: what is documentary? In fact it’s part of a larger story and a way of editing, half-truth filtered through the eyes of one person. Moreover, what you remember has relatively minor value too. To what extent is what you remember true, distorted or manipulated?

MT:

It always ends up being interpretation, whether by historians, journalists or photographers.

THB:

It’s a contradictio in terminis: ‘a real picture story’. Pictures are always ambiguous.

MT:

Those are your words: ‘a real picture story’.

MW:

Yes and I consider them to be plausible; real-images-in-a-book; a real storybook.

THB:

It doesn’t say it’s a picture story on reality.

MT:

The medium of photography is pre-eminently considered suitable for recording reality.

MW:

That statement is disputable too. What truth hides in a family album for example?

MT:

Exactly, it’s decorum. “All the world’s a stage; And all the men and women merely players.” (from Shakespeare’s As You Like it, 1599).

Now I better understand the notion of ‘truth’ in this context. Then what follows are the collages: cubist-alike, mirrored images of Martha’s body, in most cases ‘decapitated’. Some rather grotesque: ‘stacks of busts’ for example. And because in his annotations he uses words as ‘bound Bra good’. What could the qualification ‘good’ have meant to Henry?

MW:

It meant a figure, a grade; he succeeded in making successful pictures. He also used marks like ‘xxx’, or ‘ok’, both in the diagram and the captions to the collages.

MT:

If I understand it well, he meant ‘good’ in terms of technically successful?

MW:

Henry sorted things out, labeled everything, made classifications, gave grades. Although each picture speaks for itself, he was preoccupied with categorization and classification.

MT:

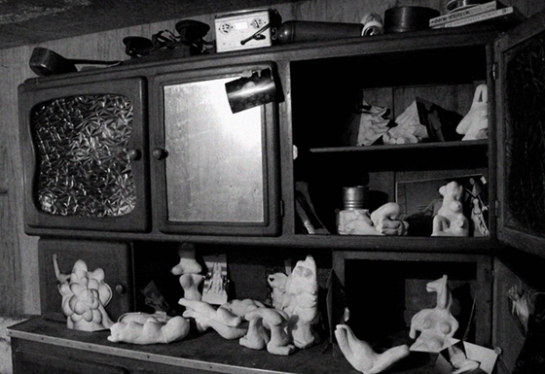

I asked so because ‘good’ is a sesitive term in this context. One could easily discover a logical connection between the ‘clay figurines’ from the late 1980s (reminding me also of André Kertész’s ‘Distortions’) and the ‘cut-outs’ from the mid-1980s. From the epilogue I understand that Dorothy and Edward discovered the collages in the deserted home after Henry moved to New Jersey. Did he make the cut-outs before the divorce and the figurines while living a hermit’s life in the forest?

MW:

Martha left right away and Henry was left alone, while his workroom was a mess. That’s the moment he started making collages. Later on in the woods he used clay. It’s important to know that Henry stopped taking photographs after Martha had left. With the leftovers of the nudes he made cut-outs. Then he started making clay figurines with the collages as models.

MT:

That is very clear. And who wrote the captions to the figurines? An index describes the numbered figures at the end of the story.

MW:

Technical data were written by the Hackettstown Center for Arts & Crafts in New Jersey. Underneath are notes on the figurines, written from my point of view.

MT:

Why did you add these?

MW:

I felt encouraged because I was allowed unrestricted access to the material, and the existing captions only give technical information.

MT:

You did that exclusively for the clay figurines and not for the cut-outs and the grids?

MW:

Because this material represents a different chapter, away from photography. Besides, these objects where later incorporated into a collection, which creates a distance, in particular because of the impersonal captions.

MT:

It reads like a personal interpretation, let me quote the description for Fig. 11: “Rather than a body, sculpture reminds of an object. Looking balanced and elegant; no aggressive shapes.”

MW:

Yes, these are my words….

MT:

Back to chronology. Henry disappeared from the stage and made clay figurines (unbaked, in his ‘second-to-last known home’), which eventually got donated to the aforementioned Center for Arts & Crafts.

MW:

That’s close to where the figurines were found.

MT:

This is the so-called ‘second-to-last known home’, right? Figurines were on display here before being donated to the arts & crafts center. Then there’s an intermezzo with several white pages, bringing us to the art-catalog-like ‘act’. The story’s apotheosis is also sombre; what are we looking at? We see a cabin’s interior; wildlife traps made of clay; a rat’s tail; ‘Fig. 9. The ‘Henry poison station’ […].’ And in the epilogue we read that Henry finally moved to a self-built ‘last home’ in the forests of Highpoint State Area in New Jersey.

MW:

Henry started with survival techniques at an earlier stage already, he cut pages out from manuals and pasted them to the walls of his rental. Later on he led a secluded life, trapping animals in the woods. He didn’t take pictures anymore, but became a predator in another way.

MT:

Thanks very much. Finally, Taco, I’d like to ask you to comment on this ‘matter’ and on the artist’s strategy of Mariken in general. What was your contribution? When did you ‘step’ in?

THB:

We met two years ago, when the final phase of Taking Off started. We decided to cooperate so to enhance the project and work towards publishing a book in one or two year’s time. Together we worked on grant applications and production-wise I was involved in the editing and translating of texts, as well as making liaisons with partners.

I knew Mariken’s work already; I’d bought Queen Ann four years ago and was intrigued. Taking Off is a more ambitious project: three times more pages than each of the other books of the ‘trilogy’ She takes time to build up both an elaborate and suspenseful picture story. You can pick up her books after months, and they still have the same suspense. Finally, I don’t think the term ‘strategy’ applies to Mariken’s way of working, it’s more intuitive than strategic.

Translated by Mirelle Thijsen, edited by Taco Hidde Bakker and Mirelle Thijsen

Pingback: Taking Off. Henry My Neighbor | omfotoboken