A GUEST IS A GIFT of GOD

Mirelle Thijsen (MT)

You and Rob Hornstra are ‘partners in crime’ in The Sochi Project. You have visited the North Caucasus, one of twelve economic regions of Russia, numerous times between 2009 and early 2013. Reading the text on the inside of the back cover of the recent year-publication The Secret History of Khava Gaisanova and The North Caucasus, how and when did you become victims of the violence, corruption and abuse of power that have plagued the region? Would you name a few examples?

Arnold van Bruggen (AvB)

Corruption is something you encounter there anyway. We have often experienced that bribes had to be paid. We had to put in some roubles in our driver’s license or passport. Once we were picked up in Dagestan and an official asked us: “If you don’t want to be troubled by one of us, we want you, right now, to count down this amount of money”. And he mentioned the amount. We did not do it. That is a form of corruption and abuse of power at the same time. Violence you encounter when you have to deal with armed police men, and as soon as you are intimidated by an anti terror brigade that arrested us and threw us against a wall in a basement, without saying a word. Anyway, this is dwarfed by what happens daily to the residents of the region themselves. We experience everything on a small scale. We are treated gently because we are foreigners. If you hear the stories of the people we visited, those are much more shocking.

MT

But are you allowed to enter the region? After all, they know the cases you bring forth related to your investigation. Are all areas are accessible for you?

AvB

No, not all areas are accessible. For example, a Dutch diplomat was summoned to the Russian security service (FSB) and had to explain who we are and what we do in Russia. The diplomat told us afterwards that all our movements in Russia must pass through the FSB. And that’s quite a restriction of freedom. That is the case, since the last journey through the North Caucasus, when we were arrested in North Ossetia. We were dragged before a court; they wanted to deport us from Russia.

MT

Are you afraid now, after those experiences?

AvB

No, we feel safe as foreigners. We do know that we are being monitored. If we have bad luck, we will end up two days at a police station, or at the courthouse.

MT

The secret history of Khava Gaisanova is the fourth annual publication in The Sochi Project and was recently published. On the book is the description:‘This book is a penetrating account of their travels.’ What exactly does that mean?

AvB

Yes, indeed, The Secret History is the annual publication for 2012 and 2013. The book is titled such because it is about a violent region. That makes it intriguing. The publication contains horrendous stories of human rights violation, of loss, of murder and manslaughter, the full package. That makes this volume more intrusive than Sochi Singers, for example. I would not label Sochi Singers as inquisitive. And the annual publication on Abkhazia, Empty Land, Promised Land, Forbidden Land (2010) is a new kind of travel book, playful, an approach to Abkhazia as fairyland. Although, serious issues are addressed in Empty Land, namely, the turning point of the country. At the same time it is a cheerful and light book. In comparison, The Secret History is fairly black.

MT

Yes, indeed. The Secret History is shelved as massacres. Is it for the first time that the result of such a long-term research period is between the covers?

AvB

This also applies to the Abkhazia book. In 2006 we started the work-in-progress, and the publication came out in 2010. Actually, such duration applies to all books published so far. At its core, the Sketchbooks Series are books about journeys. So is Sochi Singers also the end result of several trips. What makes the difference? The subject is much more defined and delineated. Then again, Sanatorium is based on two trips.

MT

The title is quite suggestive: with The Secret History, it feels more like living through the history then reading a history book.

AvB

Things are revolving around each other: the even-numbered chapters tell the story of Khava. The odd-numbered chapters are the stories in which history unfolds. Sometimes chronologically, then again thematically addressed. Be that as it may, it is a history book, a history of violence in the North Caucasus. Describing how it is for the population to live in a conflict zone for generations, having to do with deportations and poverty. Living in those circumstances, non-stop.

MT

Is it the case that in The Sochi Project the local story is symbolic for the larger historical events?

AvB

Yes, exactly.

MT

Let’s look at teamwork and collaboration. Art practice as research and interdisciplinary collaboration is intriguing. Who is doing what and when? And then of course in this case you have the full package of crowd funding/updating a website/deciding travel destinations/conducting historical research/determining content and design of a publication/consultation with graphic designers/managing self-published photo books. How do you manage to do it all?

AvB

Yes, I will scroll down the list. When it comes to crowd funding, we more or less stopped campaigning, because the project is coming to a close. That money still coming in is marvellous, and we definitely need it, but we are currently very much involved in organizing and distinguishing the overall project content. We have no time to raise money. Previously, that part of the project ran through Rob’s lectures, and via personalized mailings we both sent to large groups of contacts. The backbone of the crowd funding system is managed by both of us. I do the project finance, Rob is responsible for the call for donations: soliciting donations, supervising the contact with the donors and sending the newsletter out, which again, I write. It’s pretty meticulously planned and we both perform different tasks. The forefront of crowd funding has many different faces. I post on Facebook. This activity has become a kind of newsletter with lots of followers, interacting with our promoted posts. Facebook has become an important social utility and platform for The Sochi Project. The website now under construction, which I am building, here at Prospektor office, together with a trainee, is the final presentation of The Sochi Project.

MT

And your travel destinations: Who decides where you are going?

AvB

That differs from time to time. I decide where we’re going and why. Because I consider a location interesting from a historical point of view. And Rob considers, in return, what we’re going to run into and what kind of series he could start making. He photographs not just series, but also stories about what and whom we encounter along the way and while strolling through villages and cities. I’m in a leading role because there is a historical context and urgency and I need the stories, and Rob investigates what subplots we might encounter. He is confident that on all these locations, which I handpick, so much is going on that we have a wide range of potential stories.

MT

Would you please apply this issue to The Secret History of Khava Gaisanova? What travel destinations are chosen, and what you may encounter on the journey?

AvB

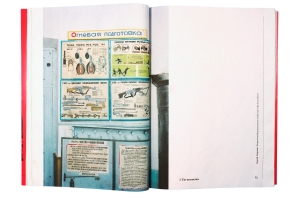

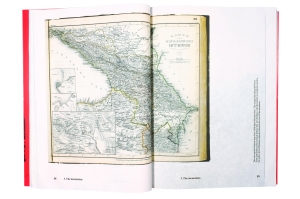

Yes, for example, if we decide to go to Dagestan, I recall, I want to go to a particular village, knowing something happened there in the nineteenth century. That in itself is not particularly of interest to Rob, but what is interesting, is the fact that an armed uprising is taking place right there, right now. We know what to get hold of in a capital city; there are many interviews to collect. We know we should be moving into the provincial towns, as they are prototypical cultural areas of the region. When we go into a republic we have a pretty good idea what we are looking for. What places we should visit. The villages are interesting because of their history, the capitals because of the people who live there, and the provincial towns show the true face of the country. In such a way a story unfolds. The North Caucasus, we noticed, is interesting because of its stories of wrestling. Rob gets his hands on this information, and considers a series on wrestlers. And my intention is to speak with a couple of trainers and athletes. As a result Rob consistently visits each gym, in every town and city, by taxi or by car. Everywhere I want to go, from my perspective, we at least visit the local gym, which is always present. Like in the beginning of The Sochi Project we visited the cultural houses playing an important role in promoting cultural and educational activities. Rob devoted a large series to the palaces of culture, these major clubhouses in the former Soviet-Union. Thus, the historic location I trace gains a sharp photographic dimension.

MT

How do you conduct the historical research regarding The Secret History of Khava Gaisanova; Where do you start?

AvB

Over the years I know a lot has been written on this region. At home I have a library full of publications on the Caucasus and Russia: history books. I also find many suitable journal articles on the Internet. With a large folder full of articles I have read, I depart for the North Caucasus. For example, I pick up the information that in the region, in a village, radical Muslims caused an upheaval. That conflict is being mentioned in the posts I read, convincing me we should go there. Then I investigate to what extent that specific village played a part in history, so the research conducted is at times rather fundamental. I work with documentation from several human rights organisations: Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International reports, journalistic articles and news feeds as well as historical books, in order to get a overall picture of a country before we get there.

MT

Could you name a village?

AvB

For example Gimry. This is a village we eventually did not reach, because the police arrested us. But certainly a location I had wanted to visit for this reason alone. Another village, I’m glad we did visit, is Kirov Abbasi, mainly inhabited by Salafists. Many in-depth interviews were conducted there and Rob took some appropriate pictures.

MT

Please elaborate on the content and production of publications. The division of tasks needs to be properly coordinated, I can imagine.

AvB

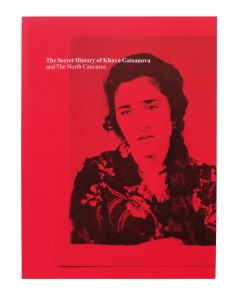

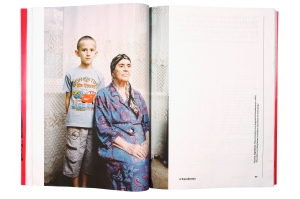

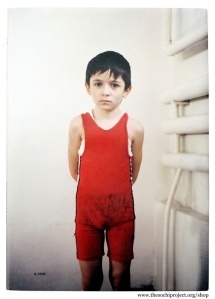

Yes, indeed, that is time-consuming. Rob found it hard choosing a focal point for his series. What will be the photographic record of the North Caucasus? In March 2012 this had taken shape. We were looking for a strong common thread: someone being symbolic for that region. The story of Khava Gaisanova sprouted from the idea to write about the North Caucasus. She started to be a reference model for that region, for several reasons. First, her personal history reflects, in a way, that of the North Caucasus. Secondly, she lives and works, in social and political terms, in a very interesting area in the North Caucasus. And a third reason is that her family photographs are wonderful. Her personal pictures, such as the portrait of Khava on the front cover, captivated us in such a way that they remained in our hearts.

MT

And the small photo album, whose idea was it to insert it into the book?

AvB

This also has been a long-running process. Initially the album was intended to be a separate section in the book. It was meant to be a small book, but it happened to be impossible to bind it between the newsprint sections. We also considered an oversized reproduction of the photo album: as large as the book. Thereby the album lost its magical touch. And by inserting it into the book, the album becomes a surprise, a present, which I consider is very appropriate to the title. All of a sudden you reveal a small photo album of Khava. It is intimate and quite literally a fascimile of the original photo album. Fitting ‘the secret history of Khava Gaisanova’. All of a sudden such a secret present drops from the book.

MT

How would you describe the involvement of the graphic designers Kummer & Herrman in this long-term documentary project?

AvB

That collaboration is intensive. Kummer & Herrman is not a third party anymore, but definitely a partner in The Sochi Project, particularly in recent years. The role of Jeroen Kummer is pivotal for the project. He contributes at an increasingly strategic level and on design issues. The production manager at Kummer & Herrman, fully committed to the final year of The Sochi Project, is Heleen. She is in charge of coordinating the production process with Aperture, as well as the exhibition programme. Over the last five years, Kummer & Herrman has come to play a crucial role.

MT

Both you and Rob consult the designers on layout, typography and design of a publication?

AvB

Yes. A third of the meetings I attend myself. I take part in the overall discussion at the start of the project, which involves brainstorming. Somewhere midway we are discussing the first drafts and outline. And we meet in the final phase of the project, when everything comes together. Rob is far more often present at Kummer & Herrman. First of all for practical reasons: he also lives in Utrecht. Secondly, due to Kummer & Herrman’s involvement in picture editing. Which photographs do they consider crucial for the publication? How is the sequencing of images and page layout? How is the book taking shape, incorporating texts and series of photographs? Rob and Kummer & Herrman hold intensive consultations on these matters.

MT

If you look back at the partnership with Kummer & Herrman, then and now, to what extent has the program and the partnership changed over the years?

AvB

At the beginning the collaboration was less intensive. Then it was more of a client-contractor relationship. We said: make this website. Think of a good book, we can make for very little money. The partnership was ad hoc. Bit by bit it turned out we needed more and more products: postcards, posters. We published more books, curated exhibitions. The red newspaper On the Other Side of the Mountains (2010) was produced in between yearbook productions. The Sochi Project became a full time occupation. And their contribution is merely strategic in nature. Kummer&Herrman are fully engaged, conceptually as well. The newspaper On the Other Side of the Mountains is their product. We indicated that we want a loose-leaf publication, and they confirmed it is possible to make something mobile. Then we put the puzzle together in Rob’s attic. ‘The puzzle’, meaning, a newspaper can be a genuine newspaper but at the same time a portable exhibition. It worked out to be an excellent partnership!

MT

Both in book technical terms, and in terms of design, I notice resemblance between the red newspaper and The Secret History of Khava Gaisanova. And both are in newsprint.

AvB

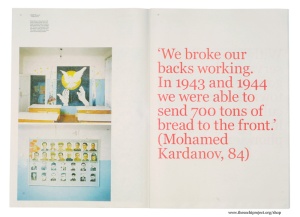

Yes, absolutely, they have something in common. You might even term it a sequel publication. The book has the same design and same appearance, and contains quotes accordingly. And, in particular, the choice of paper is similar. I also consider the content of both books complementary. Both address the North Caucasus, although that is a very straightforward comparison. Both publications are made with a sense of urgency to tell the stories. And consider the added urgency of newsprint and design. With quotes and headings. In order to tell – nearly scream – the story from the other side of the mountains, and not to linger at the sea resort Sochi.

MT

What is the story of Khava, the protagonist in your recently published publication? What’s so secret about her story? To what extent is her life history symbolic of the history of the North Caucasus?

AvB

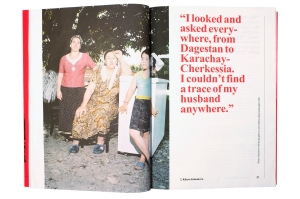

I can summarize her life briefly. She was born in exile in Kazakhstan, where her parents have returned. She has turned back to the North Caucasus and after arrival her grandmother married her off to a man, a passer by. Then she witnessed a series of wars, which involve the war in Chechnya, and in her own district, the Prigorodny district, in the early 1990s. Khava resides in the region of Beslan where the infamous school hostage-taking took place. The entire history of the North Caucasus, both those in the nineteenth century, by the conquest of that region, as well as the latest terrorist attacks, are part of her life. Her husband was kidnapped in 2007. This makes her personally reflective of the story on the North Caucasus, which is currently a miserable area, where human rights violations take place on such a large scale. Please realize her life history is not a summary of the history of the North Caucasus, but her story has links with numerous events there, and that makes her case a typical example of the life story of a woman from the North Caucasus. With all the dramas that this entails. I could also mention a hundred other women for whom that likewise would apply. Important is the fact that she lives right in the hart of the North Caucasus therefore is connected with Ossetia and Beslan. This aspect applies to fewer people.

MT

But why the title: ‘the secret history’? What’s so secret regarding her personal history? Furthermore, ‘the secret history’, chapter 16 in the book, is where her story ends. I wonder what precedes it.

AvB

‘The secret history’ refers to the creation of the story, rather than about her personal history. It’s ‘secret’ because the story remains hidden, in consequence of the adverse conditions in the country where Khava lives. What is it like to travel in the North Caucasus as a journalist, and to write this kind of stories? While working you’re constantly obstructed. Working as a journalist is made difficult. Finally, we even were dismissed from her village, sent away by the police and the Immigration Department. That is in short ‘the secret history’. And that opposition – that struggle – ties in with the story ‘on the other side of the mountains’ that we want to tell. It is very difficult for journalists to tell that story.

MT

In chapter 16 do your meetings with her come to an end?

AvB

Yes, because at that time we are taken away by the police.

MT

Could you briefly outline what precedes this event. And please focus on Khava and her nagging question: where is my husband?

AvB

How her personal history unfolds is described in the preceding chapters, and how her husband one day disappeared, on his way to Vladikavkaz, in his car and accompanied by a neighbor. How they come back from Kazakhstan, where she has had a pleasant Soviet youth. A typical Soviet youth. She was one of the pioneers. They went to the cinema. Khava lived in that multicultural city. Very different from the North Caucasus, a region which is not multicultural, in the sense that there are people from across the former Soviet Union. Where life is much stricter because of social norms and rules which apply there. She was born in exile. Her story starts with the deportation. And before that, with her ancestors chased from the mountains, hunted by the Russians. I tell the story in a series of meetings with her. We often met at her place. One time we went with her to the school where she teaches, other times we sat in her kitchen. Yet again another time we sat on the street, where she has her mini fridge with bottled water. It is a series of meetings based on which I intended to tell her life story.

MT

How does the journalistic work proceed? What do you have to do to be able to tell your story? You explained already, you start out carrying out historical research, on the Internet, in books. But, I think, interviews with people on location are an important source of information.

AvB

Yes, interviews are the main source. My stories are based on these interviews. How that works in practice? On the one hand I collected information from lawyers and human rights activists, including NGOs. On the other hand – what we really love – is to go to those spots where things are happening. That makes a region interesting. And just going up to a person’s house and ringing the doorbell. Or encountering people on the street, and seeing which stories emerge. That may be a story of a brother or neighbour, as we pass through a village. And we leave the village with beautiful, suitable stories.

MT

So, the process is actually pretty spontaneous?

AvB

Yes, but only partly spontaneous. However, before such a meeting takes place we have taken a few decisions: what area do we go to, which village do we want to visit, what city. Then we have our informants who suggest you should visit such and such place. Thus, we receive both suggestions beforehand and there are people we just happen to meet.

MT

Would you be able to describe one or two encounters with people in the area, aside from those with Khava. Was it another encounter that has left a big impression on you?

AvB

For this book, an encounter which left quite an impression on me, is a conversation with a police officer who had thrown himselve on a grenade to protect his colleagues and who thereby is confined to his bed for the rest of his life. In a room, with young daughters jumping around him. He has no legs, and lacks a arm. He has bad hearing and damaged eyesight. He sits there on his bed and hopes his children and wife come home, and tell him some stories. That is a source of information and a depressing story. With this story I try to show the reverse: the many victims in the government due to the conflicts. And then there is the comment that the police officer made: ‘I threw myself on top of that grenade in a whim in order to save my colleagues, but when I look back, and see what happened to me, and what my colleagues actually did, then I have sacrificed myself for a bunch of cowards’. I think that is a very nasty note. Well, because it evokes strong feelings of bitterness. “Why have I done this for God’s sake. Which particular case I have served?” A case in which he no longer believes.

MT

Would you give a brief explanation for the sentence in the book: ‘the Caucasus is more than conflict and refugees, fundamentalist Muslims or games’.

AvB

I don’t recall in what context the phrase was used, but I think I wanted to say that a lot of people try to lead a life as comfortable as possible, with a vegetable garden, a local café and a job. More than half of the population living in that region is unemployed. In the end I’m afraid of – in the process of making such a book – de-humanizing the story. That it becomes just a big chunk of grief, misery, abuse, torture and loss, while someone like Khava also has fun times. We have shared dinners with her, drank fruit juices, eaten delicious meals. It’s people like her who, indeed, enjoy life. That feeling should also radiate from such a book. I don’t want to suggest the North Caucasus is just a big black hole.

MT

A sentence, on page 26 in chapter 1 (‘The North Caucasus’) of the English-language edition, describes this book is a ‘work in progress’ you already have started in 2007. Would you please elaborate on that?

AvB

Yes, it means visiting the region several times. The book is not so much the result of a journey, or a survey, but rather the result of ongoing research, advancing insights.

MT

How many times have you been in the North Caucasus?

AvB

I do not know exactly, but I think in the last four years we have been seven times in the region?

MT

And is the project now completed?

AvB

Yes, now this book has been launched. But in May we both go back to the North Caucasus. And I think I will come back more often. There is plenty to tell about that area. Also, I think it is important to keep focused on the Caucasus. I want to continue writing about that region, although the Sochi Project is almost completed. In May we will go visit again a number of ‘protagonists’ whom we consider important for the project. We are curious about the lives they led over the years. Especially we are interested in the people we have met in the very beginning. And we will go to places where we haven’t been back at all. Such as Krasny Vostok. How has life unfolded in that village from one moment to the next? We probably want to depict that story in images, so a development becomes clearly visible, in addition to what’s going on in the cities.

MT

And what does this term, posted on your website, mean: ‘innovative journalism’ in the 21st century, particularly in relation to documentary photography by Rob Hornstra and creating photo books?

AvB

We are most innovative in implementing crowd funding. And that we are called, ‘innovative’, being rewarded the Canon Price for innovative journalism, lies above all in the fact that we use crowd funding, in order to produce conventional publications (such as the red newspaper), and add new meaning and content to journalism. These points are mentioned in the jury report. We use a traditional medium, such as a newspaper, and give new meaning to it. So the innovative aspect relates to a new way of dealing with traditional media, also with regard to the books. How do we apply state-of-the-art crowd-funding applications, use Facebook, Twitter, and spread the message worldwide? And at the same time try to translate the work in process into the most suitable form of publication. For example a photo series about Christmas trees, by way of Christmas cards. The newspaper also becomes an exhibition, and this recent book is really more of a newspaper. In such a way, all of our publications are not really what they seem. This makes you feel as a reader slightly unbalanced. And maybe, proclaiming the message even stronger.

MT

How does your text relate to the pictures made by Rob Hornstra?

AvB

An interesting aspect is that text and image production almost always run parallel. That is why there has been cross-pollination between our contributions. Because we have made all those trips together – Rob has witnessed all interviews, everytime he took pictures of local people, I was holding the flash – in such a way text and image are being intertwined. They tell the same story, but in different ways.

MT

You have explained how you prepare for a trip, how you are doing oral history, and conducting interviews. And, once you’re home, how do you proceed?

AvB

You mean working out the project, the writing? It starts with a whole stack of notebooks that I crisscross and I summaries the interviews in Word. In order to be able to search and properly find material on my computer. And then I start to write based on all the experiences stored in my memory, and all I consider relevant in the notebooks. That process is a huge battle, time and time again. A fight against time and how the hell am I going to tell all those stories. How to create an articulate storyline and which stories fit into it? How to kill your darlings?

MT

How much time do you spend on the writing?

AvB

Well, each book has been different and has been challenging in its own way to write. Sanatorium I wrote while we were on location. The same counts for Sochi Singers. The stories for The Other Side of The Mountains I have collected in a few weeks time. And occasionally written out. Empty Land, Promised Land, Forbidden Land is a fairly bulky book. All in all it took me half a year to write. And regarding The Secret History I have written sections over the years. And in 2012 I have been writing non-stop for a period of three months. The year before that it had to become a mature story.

MT

Who came up with the idea to make Khava a protagonist? When was that?

AvB

In March 2012, after our trip. I called Rob and said: “I’m not sure, but I think we need to make Khava the main character.” And pretty soon after that we went back to the North Caucasus. It was exciting to submit this request to her: “We want to find out everything regarding your life story over the next few weeks, and use your personal history as a storyline for a book”. If she had said no, while we were there, we would have been standing empty handed. Then we would have had to figure out someone else, right on the spot. Then the story would have been less attractive, because the personal history of Khava is fairly unique compared to a hundred similar stories, due to where she lives and the way she looks.

MT

Describe one-day-in-the-life-of Arnold van Bruggen and Rob Hornstra in the North Caucasus. What goes well, and what goes wrong?

AvB

Each day is different. One day we are shooting pictures at a wrestling school for a Sketchbook. The next day we are locked in a police cell for a day and being interrogated. And we worry a whole lot about the fact that we miss a day and the authorities require money from us. Yet another day we crisscross the entire Caucasus racing after a quality story. From Vladikavkaz to Ingushetia. And once we are there, we visit an bombed liquor store and take pictures. And on the way back, we stop in another village for something to eat and for a story at this or that location, and off we go, back to Vladikavkaz. We may also one day dig deep in a village and interview ten people and afterwards, late at night, step back in the car, stuffed with food and drinks and many stories. Much depends on chance, on the set of circumstances, and meeting the right people, that like to talk and help us further. Other days are useless. When everything goes wrong, I consider it such a loss. But still, these days might deliver very good photographs. When Rob develops a few weeks afterwards his analogue films , it turns out, on that useless day, he made a beautiful portrait or recorded an extraordinary landscape.

MT

Back to the book: The Soviet Union tried to portray the inhabitants of the Caucasus as ‘noble savages’.

AvB

Yes, noble savages. They tried to folklorize the Caucasus. Russia and the former Soviet Union are for one and a half century in conflict with the Caucasus, in an effort to submit the region to their own governance. The opposition was persistent. What they eventually have done is, to try to highlight the local traditions, such as the costumes, dance and folklore, in order to brand them as ‘Soviet’. Look, what a multicultural Soviet Union! See what an authentic dance styles! What a beautiful people! Look what kind of steel they forge! Everything else, the opposition itself, the ideas and the cultural system of the region, as well as the standards and values of that community, served to be destroyed. This strategy was supposed to blend into the thought on equality of the former Soviet Union. Equality for men and women, destroy all traditions, such as marry off and blood revenge. To this end served the plan of action to first lift the folklore above the culture. The folklorization of all those subcultures, that’s what it was all about. It was a control method; the Caucasus had to be made manageable.

MT

You mention all kinds of people, different nations: the Ingush, Cossacks, Ossetians. What do these people think of each other? How are they similar and how are they different?

AvB

I think these nations have a lot in common. These are all mountain people. Cossacks are small nations coming from Russia. They live in this region for so long, that they identified themselves with the North Caucasus. They wear the same clothes; have a kind of caps on their heads, by way of a hat. They are riding the same horses. The hill tribes are pulled towards each other. The distinction is mainly in the languages they speak, in the belief that they adhere to. Ossetians and Cossacks are Christian. Ingush and Chechen are Muslim. And some cling to an indigenous faith. Furthermore, those people speak about forty different languages. Mutual differences in tradition and folklore are clearly visible, and they know they are very different one from each other. What I mainly see is that Soviet image of dancing mountain people on a beautiful grassy plain, to put it very disrespectfully. That cliché-image could be applied to any of these peoples. To what extent the mutual relationships actually differ, is for the connoisseur.

MT

What does the ‘hospitality’ of the inhabitants of the Caucasus involve?

AvB

Hospitality stems from the local traditions. A guest is a gift from God. That notion is deeply rooted in the genes of people, and in the culture. It is honourable to be a guest. That radiates toward your neighbours, towards your environment. And if you have a foreign guest, that is very honourable. It doesn’t matter how poor they are, people will pull out all the stops. And if that doesn’t happen, you know right away that you’re not welcome! That happens every now and then, if you are after a difficult story or as soon as you deal with people who gained too much power in government. The extent to which people are welcoming you is a good indicator of where you have ended up.

MT

Different conflicts and guerrilla wars are discussed in the book. Would you be willing to address them briefly? The Prigorodny conflict and the Second Caucasus war, the Chechen War.

AvB

In the secret history I have bundeled up all the conflicts in ‘the second Caucasus war’. When you consider what has happened over the last twenty years, and far before that, you might even speak of a broad revolt going against the regime in Russia. There is so much upheaval: all these conflicts, which are called ‘wars’, such as the first Chechen war, the war in Dagestan, the Prigorodny conflict. See the conflicts as a whole – a second rebellion against Russia, after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. One is an artificially created conflict, the other a struggle for independence, as in the case of Chechnya.

MT

To conclude, I would like to talk with you about the final publication. It is to be an atlas, I understand. That in itself explains a lot about the way in which the content material is incorporated. An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus. The grand finale. Why is Aperture publishing this book, in October of this year? Why will it not be a self-published publication, as done with the previous books? I always considered this an act of progressiveness and desire to keep everything under your personal control, thereby circumventing the institutionalized world. To what extent will this last book be different from the other publications so far? And what are you planning together in preparation? Where do you go from here?

AvB

Yes, we have now achieved our goal and work towards the Olympic Games 2014 in Sochi. The annual publications emerged from the idea to bestow the donors an exclusive gift. The first year publication is a limited edition of 350 copies: Sanatorium was only available for donors. And the latest publication involves a print run of 2200 books, both a Dutch and English edition. And besides, it is a commercial edition, sold in bookshops. From the start, we wanted the final publication to achieve large impact, a larger sale, inorder to be able to tell the story to a large audience. In this way it is well distributed, and launched by a renowned publishing house. It is both a major choice and strategic move.

The final book is comprehensive. The other books were in a sense subchapters, dealing with a regional topic, about a certain area. This book brings all these stories together, and more. The final publication is compiled according to a different plan, another schema. It takes you from start to finish through that region, along with the stories that we have told over the years. Also the stories that are told in radio interviews. This is Sochi, a summer resort that is transformed into a winter Olympic games city. That is in itself a bizarre ferrytale. Look what is happening on the other side of the mountains, there is a war going on! And to the South is a small republic: Abkhazia. In a few sentences you have the compact story. That will be published in the final book. In a wave motion walking you through the area, taking of at the winter Olympic games, and seen from the wonder and amazement with which we started this project.

We go once more to all these areas. In March we visit Sochi and Abkhazia. In May the North Caucasus. And that’s it! Meanwhile we are going to finish this final book. In fact we already have started. Because it is such a large edition of 5000 copies, published by Aperture, and the book is to be presented this fall, we are close to the deadline. I’m going tomorrow to Texel in solitary confinement. I have to start typing, writing and do editorial work to get 80% of the book ready. Following the two upcoming trips, in March and May, we manufacture and deliver another 20% of the material. In principal the book should be ready for production in May, and printed in October, just in time for the upcoming exhibitions.

MT

I will not hold you up any longer! Jeroen Kummer explained that this book is a ‘retrospective’; is that how you would describe it?

AvB

All previously released publications have propelled and produced this final book. From an objective point of view, this is, from the very beginning, the one and only intended publication covering The Sochi Project. And it was always nicknamed the ‘atlas’. The notion is applicable: we have mapped the region in four years, and now we are building an atlas on the area. And all those other books are to be considered subchapters. Anyway, earlier annual publications and the Sketchbooks series are constructive works towards the final publication. In addition, the publications have become much more substantial than the notion ‘subchapter’ suggests. Just put all the books aside, and combine all of our visits, then you achieve this final annual publication on The Sochi Project. It reflects the sum of all the stories we’ve collected.

copy editing by Nicholas W. Jankowski